We’d just gotten the win in our final league game and were gearing up for 2+ hour bus journey.

It put a bit of a positive spin on an otherwise underwhelming league campaign.

We had a few weeks off before our next competitive match and were giving lads the week off training. They were on the tinnies on the way home – a few funny comments made their way up the bus!

I got home late so did up the GPS report the following morning and posted it to the team WhatsApp.

Manager straight in with a message: “Well Done Paul”

Paul had a bang average game. Nothing spectacular but no stupid mistakes. His direct marker had a similar game so they pretty much broke even. Two other players had pretty outstanding performance but not a word so I was intrigued.

The manager never really posted much in the WhatsApp and was rare to give out praise so I checked back over the GPS numbers to see what caused this.

Paul had covered more distance than everyone else by about 800m. I think he was on 11.5k. A lot for hurling, especially on a tight pitch.

Was this what the praise was for? Just covering more distance?

It’s amazing how many managers and coaches still look at total distance as a meaningful metric. Especially when we consider how much support is out there around the use of GPS and what is more relevant for monitoring training and matches.

In terms of what’s monitored I’m usually looking at high speed distance, sprint distance, number of sprints, top speed, meters per minute and accelerations/decelerations. Total distance covered is way down the list of priorities.

When using GPS, there are a few main uses for the data we gather:

1. Understanding Game Demands

By tracking multiple games, we can identify position-specific demands. For example, how much high-speed running does a half-back typically cover? Once we establish an average range, we can tailor preparation accordingly.

2. Training Activity Analysis

With a clear picture of match demands, GPS helps assess whether training activities are preparing players adequately. If a midfielder covers ~1,800m of high-speed distance in a game, we can design high-intensity runs (1,600–2,000m) or modified games that replicate this within gameplay, adjusting timings for load and recovery.

3. Workload Monitoring

GPS also helps manage player workloads over time. If an athlete covers 1.8k of high-speed running in games and 3–3.5k weekly, maintaining consistency is key. A spike (e.g., 3.2k in one session) may require workload adjustments in subsequent sessions to prevent overloading.

I’ve heard a lot about misapplications of GPS lately. Largely around players not covering enough distance (what is enough anyway?) or not working hard enough and it got me thinking:

Is this representative of a broader issue?

Are we getting distracted from what really matters? Coaching our sport?

I recently got a text (a little out of the blue) from a buddy that works full time in coaching:

“I honestly think GAA is gone mad”

I asked for a little more context so he replied:

“Everyone wants the optical stuff to be in place and look the part, but no one looking at the actual standard of coaching that happens on the pitch”

Well that got me thinking.

How many clubs invest heavily, in terms of finances, time and energy into various “supports” like wearable devices, monitoring apps or systems, cameras, VEOs, analysis software, etc.,?

How many can really justify the use they get from it but will pay so little attention to the quality or upskilling of coaches?

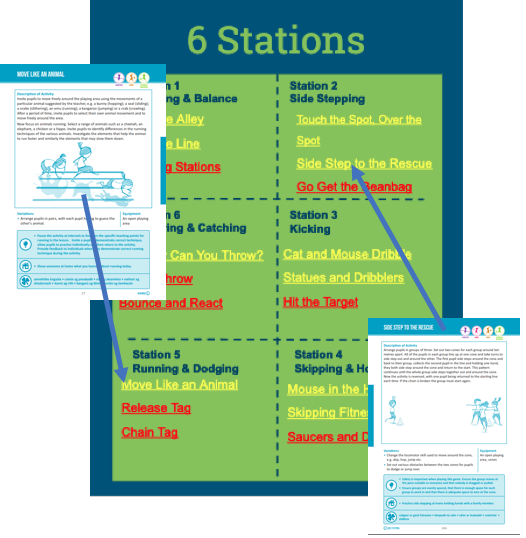

If you had nothing but a whistle, a few cones and some pen and paper, you could be an incredibly effective coach. You could massively improve your team, at the majority of ages and levels, across codes.

Quality activities.

Appropriate drills or games.

Modifications suited to the individual or team.

Questions.

Cues.

Guided Reflection.

Feedback.

All free of charge but effective!

Do teams try and distract from the lack of quality coaching by trying to provide an illusion of professionalism by putting other stuff in place? Are managers distracted by “shiny new toys” or just sold stuff they think is important?

Spending thousands on GPS to call out players who “aren’t working hard enough” because then only cover 5-6km in a game while someone else has covered 8km. What other contributions have they made to a game in terms of scores, assists, meaningful runs, dispossessions, tackles, etc.,

Do they even know what “working hard” is? Has it been identified or does a manager simply want busy fools who run around, cover loads of ground, clock up the distance but have minimal actual impact on the game? Could we instead provide them with some guidance on what hard work is relative to their position and role?

Conversations with individual players or in small groups based on positions. What do we want our inside forwards to do? With the ball, without the ball, when we’re in possession in certain parts of the field, on our own or opposition puckouts, etc.,?

If we provide clear information about these situations to players then it’s much easier to praise when done well or ask for better when it’s not. Guiding their improvement in these situations can be done through a combination of specifically designed games, individual feedback or examples from actual game situations. This is where some of the tools can be useful by showing clips or providing some objective stats.

Technology should support great coaching, not replace it.

The tools are valuable when they enhance decision-making and player development, but coaching is about more than just numbers or data. The best coaches focus on creating effective learning environments, developing relationships, and making informed decisions based on both data and experience. They empower players to make the best decisions in the toughest of situations, lead in a variety of ways and challenge all around them to make things better. Technology should be a tool that refines this process; not a crutch that replaces good coaching judgment.

The best coaches don’t just track effort; they guide it.

They don’t just collect data; they make sense of it. And they don’t just train players to cover more ground; they teach them how to impact the game.

I challenge you to trial some of the following in your next few sessions:

- Track how long you spend talking to a group of players throughout the session. What percentage of training is spent listening rather than doing?

- Count how many times you ask questions versus how often you give instructions. What is the ratio, and how can you shift the balance to encourage more player thinking?

- Keep a tally of how often you give individual feedback. Is it actionable for the player, or just general encouragement? Aim for feedback that directly helps them improve.

- Observe a drill or game without intervening. Are all players actively involved, or are some on the fringes? If engagement drops, how can you adjust the activity to keep everyone challenged?

- Before delivering an instruction, challenge yourself to explain it in 30 seconds or less. If it takes longer, simplify. Are your players spending more time listening or playing?

- Track how often you give positive reinforcement versus corrective feedback. Are you catching players doing things well, or only focusing on mistakes? Aim for a 3:1 ratio of positive to corrective feedback to build confidence and motivation.

What is more impactful? Any of the above versus the expensive coaching “aids”.

“Mol an Óige agus Tiocfaidh Siad”

“Mol an Óige agus Tiocfaidh Siad”

We recommend some fast-acting carbohydrate, mixed with protein, immediately after exercise. Flavoured milk, fat-free yoghurt, chicken sandwiches or protein and fruit smoothies are usually the best options in terms of both meeting nutritional demands and being easy to prepare in advance.

We recommend some fast-acting carbohydrate, mixed with protein, immediately after exercise. Flavoured milk, fat-free yoghurt, chicken sandwiches or protein and fruit smoothies are usually the best options in terms of both meeting nutritional demands and being easy to prepare in advance.